Hardly anything remains of this

brick-works today. The area has been

made into parkland and considerable regrowth has obliterated almost everything

of the brick-works. The only areas

remaining relatively untouched are the ramp along which the clay trucks were

pulled up from the pit and the platforms where the buildings were located. Much of the pit has been filled with

rubbish, like so many other pits around Melbourne.

The first small-scale brick works in

Montrose was opened by James Walker in 1891 at a site on Mount Dandenong Road

where the CFA Fire Station is now located.

Hand-made bricks were made from red porous clay dug at the site to be

used in baker’s ovens; and white kaolin clay used for fire-bricks. These types of clay were unique to this location. James had a store on the corner of Mount

Dandenong Road and Montrose Road that he named “Rose Mont”, said to be the

origin of the town’s name. The original

brick-works site closed in 1920.

In the English-speaking world,

the term for a kiln used to make a smaller supply of bricks is known as the

Scotch kiln. It is also known as a

Dutch Kiln or a Scove Kiln. It is the

type of kiln most commonly used in the manufacture of bricks. Scoving is the process of covering the kiln

in wet clay to seal any openings. It is

a roughly rectangular building, open at the top, and having wide doorways at

the ends. The sidewalls are built of old or poorly made bricks set in

clay. There are several openings called

fire-holes, or " eyes," made of firebricks and fire clay, opposite

one another.

Construction of a Rectangular Downdraught Kiln at Gulsons Brick Works in Goulburn NSW

The dried raw bricks are

arranged in the kilns so as to form flues connecting the fire-holes or eyes,

and they are packed (crowded) in such a way to leave small spaces between the

bricks from bottom to top and front to back and side to side through which the

fire can find its way to and around every brick. A modification of the Scotch Kiln is

sometimes to have openings in the floor like latticework, through which the

heat ascends from arched furnaces underneath.

After the dried

bricks are loaded into the kiln, the ends (or wickets) are built up, and

plastered over with clay. At first the fires are kept low, simply to drive off

the moisture. After about three days

the steam ceases to rise and the fires are allowed to burn up briskly. The draught is regulated by partially

stopping the fire-holes with clay, and by covering the top of the kiln with old

bricks, boards, or earth, so as to keep in the heat. It takes between 48 to 60 hours for the bricks to be sufficiently

fired, and they will have shrunk to the appropriate size. The fire-holes are then completely sealed

with clay and all air excluded. The

kiln is then allowed to cool gradually.

About a half-ton of soft coal is

required for burning each 1000 bricks. The exact quantity depends upon the type

of clay, quality of fuel, and the skill in setting the kiln.

A convenient size for a Scotch kiln is about 60

feet by 11 feet internal dimensions, and 12 feet high. This will contain about

80,000 bricks. The fire-holes are 3 feet apart. These kilns are often made 12

feet wide, but 11 feet is enough to burn through properly.

An early Scotch Kiln showing the way bricks were stacked and the size of timber for firing.

A kiln takes on an average a week to burn,

and, including the time required for crowding and emptying, it may be burnt

about once every three weeks, or ten times in an average season. This will

produce about 800,000 bricks that is about as many as would be turned out by

two moulders in full work. The bricks

in the centre of the kiln are generally well burnt. Those at the bottom are

likely to be very hard, some clinkered. Those at the top are often badly burnt,

soft, and unfit for exterior work.

A Scotch Kiln is of a type known as an intermittent

kiln. A Hoffman Kiln is known as a

continuous kiln. In a continuous kiln bricks remain stationary and the fire moves through the kiln with

assistance or help of a chimney or by a suction fan. Most brick works in

Victoria ended up using the “Hoffman” kilns of this type. The kilns at

Montrose were intermittent types and could not compete with the volume produced

in the Hoffman Kilns in Melbourne.

Fire Bricks, or refectory bricks are used

to line high temperature fireboxes, such as furnaces, kilns and

fireplaces. They are also used for

processes with extreme chemical stresses.

They are also used in processes using electrical or gas fuels. They also have better insulation and sound proofing

qualities and do not fracture when exposed to rapid temperature changes. They can withstand heat of up to 2,800

degrees C.

The next chapter began with David

Mitchell (1829- 1916) who is best known as the father of Australian icon Dame

Nellie Melba. Davis arrived in

Melbourne on board the ship “Anna” on the 6th of April 1852 and

worked as a mason and builder as well as spending some time on the Bendigo

goldfields. In 1856 he married Isabella

Dow, daughter of James Dow, an Engineer at Langlands foundry. (A fitter at Langlands, Herbert Austin later

returned to England to begin the Austin car company.)

David Mitchell

On the 29th of August 1904, David Mitchell bought 10 acres of land from James Walker on the eastern corner of Montrose and Cambridge roads (Lots 35 B & C). The works was situated on a small creek that flowed parallel to Cambridge Road and eventually into Olinda Creek. Mitchell became the majority shareholder in the Darley Fire Brick Company, outside Bacchus Marsh (Registered Office Olivers Lane Melbourne) in 1902 and began manufacturing of fire bricks in Montrose as well as Darley using rectangular downdraught kilns.

David built the Exhibition Buildings in

the Carlton Gardens and St Patrick’s Cathedral, Eastern Hill, just to mention a

couple of his projects. In 1859, David

had a brick-making company in Burnley Street and in 1874 he became a

shareholder in the Builders Lime and Cement Company. In 1890, he and his partner R.D Langley began a Portland Cement

factory at Burnley using Kaolin from Lilydale.

In 1878 he purchased Cave Hill Farm at Lilydale and started excavating

limestone from the property.

“Brick works of every description have cropped out within the last 2 years 6 months. Under the management of Messrs Naylor, Tranter and Derbishire, who keep things in full swing huge storage sheds, for moulded material have been erected

some 250 feet long, other buildings attached, engine house and otherwise, where the bricks of all sorts are turned out by the thousands. A good start considering the time, roads and sundry obstructions to develop such as a brick making

industry. Since the long expected railway has flown to a better land I'm told flowing with milk and honey and otherwise which had caused us of Montrose to look after it, and of our own lookout as a dark blot, and prospects unsolaced for its prosperity since the Creator, looked back on it and so leaving his huge foot mark behind in disgust as he disappeared to mould a brighter place, possibly our neighbours

doorways, Lilydale and Wandin districts; possibly the luck they have stolen has paid them.

Possibly we could expect to see a tram track to the kilns; if only bricks sold well and a dozen yards were set in full swing, and fire clay in abundance. But trade is not good enough to gratify any other attempts

at

present. Perhaps fail latter on. Roads not fit to pay to cart along. Fire clay of the very best can be got. Tiles, pipes, fire bricks and a dozen other sorts are turned out.

Very

good

assortment for the time to prove how trade runs. The works are not 10 minutes walk from the Montrose store and post office, even at this some residents a mile off are not aware of such a company as brick-works in the district to the present. Three fair sized kilns are kept going continually the clay is hawled (sic) up by steam power and the bricks of all sorts cut and set and then

pressed to finish for the fiery kilns. Some 9 or 10 workmen are kept going regular as clockwork. £60 or £70 per month ($30 to $35) worth more or less are turned out. Not so bad since developing a trade to be included no small matter.”

Richard Walker Lilydale Express 11 October

1901

But early on, David had his eyes elsewhere. In 1902, he bought into another brick making plant at Bacchus Marsh. The clay was considered superior to the local clays in Montrose and the area available for the brick works was much larger. Output was higher. In time, the majority of manufacture was undertaken there. There was already a brick works operating there, having been established in

1893 by Thomas Akers and William Wittick.

David bought into the partnership in 1898. This additional capital allowed for

expansion. On the 9th of May

1898, the “Darley Firebrick Company Pty Ltd” was formed. Mitchell holding the majority of shares. It is now known as “Darley Refractories Pty

in 1982 following acquisition of the South Yarra Firebrick Company.

In 1914, the Button family came to

Montrose. Clarence Lloyd “Clarrie’

Button was born in Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand around 1878. Clarrie died at age 73 and was buried in the

Lilydale Cemetery on the 30th of August 1951. Clarrie and his wife Mary Jane (Daughter of

WJ Walker) lived at 14 Walker Road Montrose.

They were married in 1900. Mary

Jane died in 1941 age 61. He was by

profession a Builder who had lived and worked in New Zealand and Tasmania, as well as inner suburban

Melbourne. Clarrie is listed as being

“Manager” of the brick-works in 1920.

Clarrie and his nephew William (Billy) Walker, an experienced

brick-maker, took over the company.

They greatly expanded the business.

The Darley Fire Brick Company continues today at Bacchus Marsh, on the

opposite side of Melbourne.

Fire-Lumps, Agricultural Pipes and Partition Bricks at the Montrose Brick Works.

The bricks made at the Montrose

brickworks were sold throughout Victoria.

In 1928 the brickworks were cutting 16,000 bricks per day and employed

up to 20 men. Montrose still

specialised in two types of firebricks; bricks for Bakers ovens made from red

porous clay and fire bricks made from white clay. They also produced fire lumps (for furnaces) agricultural pipes

of all sizes, perforated bricks for iron furnaces, sole tiles and gutter

bricks, as well as normal house bricks.

A Fire-Lump is a large brick between approximately 18 inches to 2 feet

long by 9 inches deep and 6 inches thick.

They cover the floor and lower side if the furnace. A Sole-Tile is placed at the bottom of a

drain to provide a firm base. Hard clay

bases do not need sole-tiles.

Layout of the works

The great depression hit Montrose

Brickworks hard, along with many other brick-makers throughout Australia. Brick making has and is a high volume, low

profit margin business. It does not

take much to tip a company over the edge.

The Montrose brickworks was finally brought to a halt by World War II. In 1946, staffing shortages were affecting

brick makers across Australia. In Victoria, soldiers returning from the

Second World War were not willing to come back into the hard, dirty and

dangerous environment of a brick works. Before the war, there were 34

brick kilns in Melbourne, employing 1034 men. After the war, there were

only 30 kilns operating, employing 600 men. There was a particular

shortage in the roofing tile industry. New homes were being built

quickly, with weatherboard being used extensively. Even though the homes

were timber, they still used fired roof tiles.

This new drying shed was built in 1931

Many of his workers had gone to war

leaving Clarrie with no choice but to sell the business to Rimingtons Nursery

in 1945. The site was used to make

flower-pots until the late 1950s, possibly until the early 1960s. This was necessary because of the shortage of

terra-cotta pots after the war. The

brick-works made pots up to 12” in diameter.

They did not use metal pots.

Rimingtons was a large wholesale and retail nursery business, plus

ornamental trees, with properties in inner suburban Kew, their retail outlet

and propagation nursery as well as Clarinda, their distribution centre and 100

acres at Toolangi as well as Montrose.

They produced a range of products from

clay, not only fire bricks, that were used for chimneys and fireplaces but also

agricultural pipes, partition bricks, fire lumps for furnaces, as well as

house-bricks. The Montrose Historical

Society purchased 700 of the Montrose bricks and had them made into a memorial

and display for this almost forgotten part of local history. In it’s day, it was the only major industry

in the town and most men at one time or another had worked there.

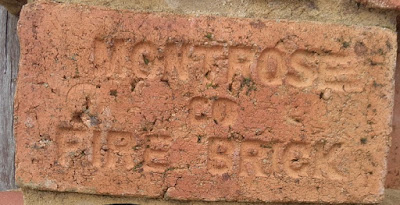

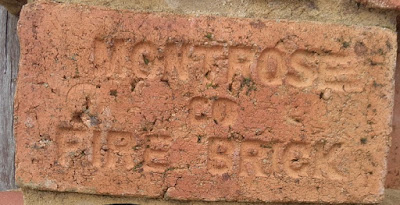

Montrose bricks can be mostly identified

by their stamps. Early bricks were

stamped “DFB Co” (Darley Fire Brick Company), “DFB Co Works Montrose”,

“Montrose” or “Montrose Fire Brick.”

Some bricks have thumb-prints, believed by some to be a counting

technique, but also made when pushing bricks from a mould (some bricks were

hand made in pairs). If you want to see

any quantity of these early bricks, I suggest you visit the Ballarat Lodge and

Convention Centre. When this

establishment was built, they used bricks from the ovens of the now demolished

Sunshine Biscuit factory in Ballarat.

Part of the Montrose Brick Display at the Montrose Shopping Centre.

My thanks to the volunteers at the Lilydale and District Historical Society for much of the information contained in this post.